DJ HIezz

https://www.mixcloud.com/housefreqs/hlezz-2017-04-28/ Housefreqs.com

Month: April 2017

FUCKING ON THE BALCONY: THE FABULOUS BUT CORROSIVE LEGACY OF STUDIO 54

The club’s penchant for hedonism overshadowed the music played on its dancefloor.

If disco was born in the underground gay clubs of late 60s New York, its coming out party was April 26, 1977 in an old Broadway theatre at 254 West 54th Street. If it wasn’t disco’s greatest club, it was certainly the most dramatic. Studio 54 was conceived as grand theatre as much as a club and it showed in the ambition poured into it by its owners Steve Rubell and Ian Schrager, as well as the woman who conceptualised it, Carmen D’Alessio. Whereas most of the New York underground club scene had been about equality and fellowship, Studio 54 was the most public expression of the veneration of celebrity, glamour and glitz, epitomised by “The Man In The Moon” on stage, inhaling coke from a glittery spoon.

Having gestated in the underground parties of the Loft and the Gallery during the early part of the decade, by 1977 disco had already become a commercial force with New York’s triumvirate of record labels – Prelude, Salsoul and West End – already established alongside the arrival of the disco-conceived 12” single two years earlier.

If disco was born in the underground gay clubs of late 60s New York, its coming out party was April 26, 1977 in an old Broadway theatre at 254 West 54th Street. If it wasn’t disco’s greatest club, it was certainly the most dramatic. Studio 54 was conceived as grand theatre as much as a club and it showed in the ambition poured into it by its owners Steve Rubell and Ian Schrager, as well as the woman who conceptualised it, Carmen D’Alessio. Whereas most of the New York underground club scene had been about equality and fellowship, Studio 54 was the most public expression of the veneration of celebrity, glamour and glitz, epitomised by “The Man In The Moon” on stage, inhaling coke from a glittery spoon.

Having gestated in the underground parties of the Loft and the Gallery during the early part of the decade, by 1977 disco had already become a commercial force with New York’s triumvirate of record labels – Prelude, Salsoul and West End – already established alongside the arrival of the disco-conceived 12” single two years earlier.

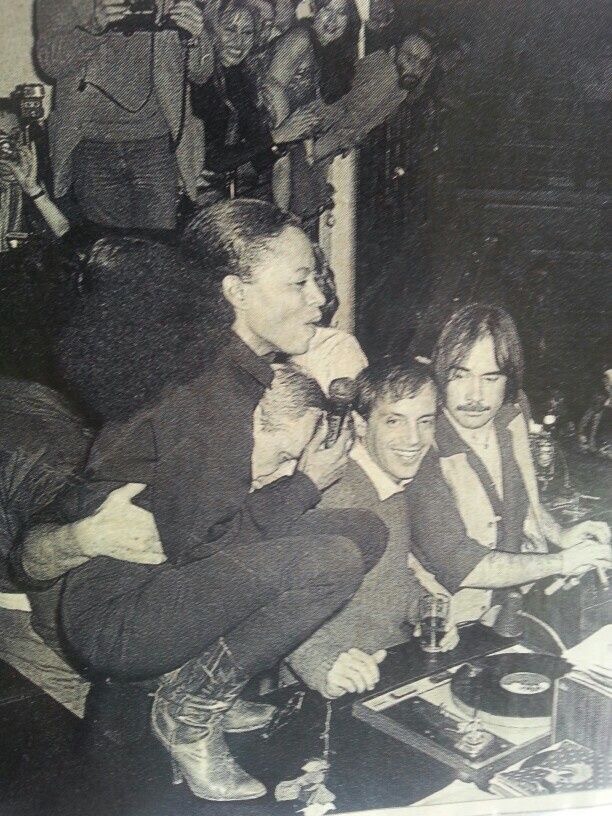

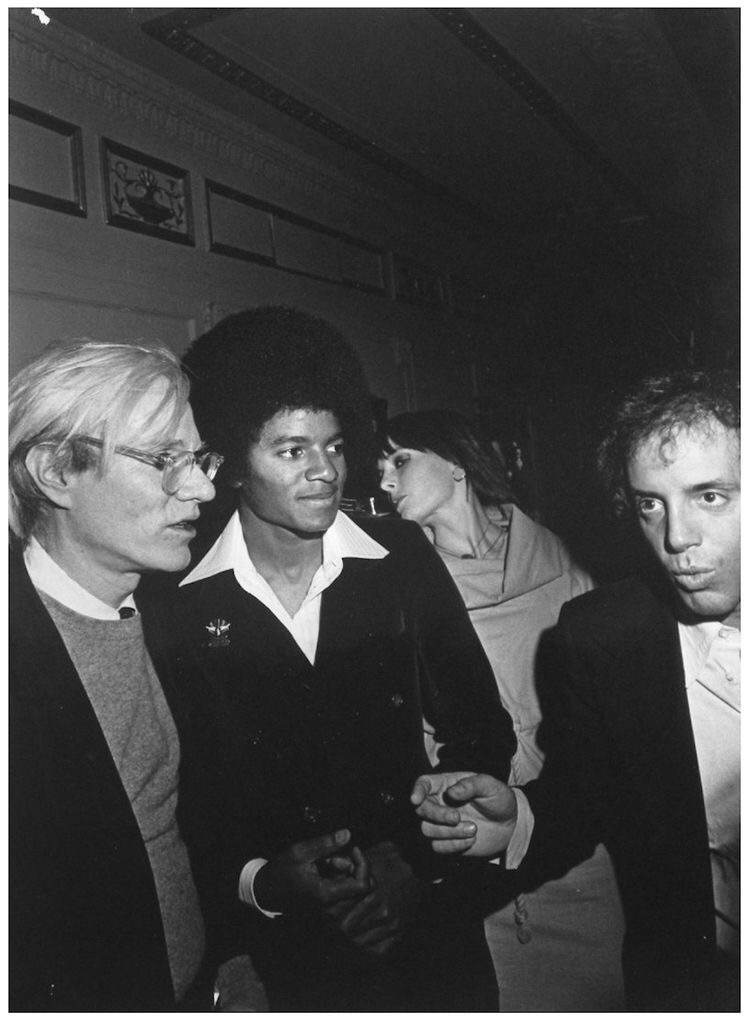

On the opening night, an array of celebs duly showed up, with Bianca Jagger, Brooke Shields, Cher and Donald Trump smiling for the cameras. In the chaos of the opening, there were almost as many left standing the wrong side of the velvet rope, among them Mick Jagger and Frank Sinatra. A party for Bianca Jagger’s birthday a few weeks later, thanks to D’Alessio’s brainwave of getting Bianca to arrive atop a white horse, was the publicity coup that helped establish Studio 54 as the go-to disco club of the moment.

The resident DJ, the much-loved Richie Kaczor, had been plucked from midtown gay club Hollywood before arriving on West 54th Street and, although a more commercial sound was required in a space so large, Kaczor managed it with grace and elegance. It was here, on the floor at Studio 54, that Kaczor broke Gloria Gaynor’s ‘I Will Survive’. It had originally been the B-side to ‘Substitute’ but it was Richie who flipped the 12” and turned it into an anthem and worldwide hit. “Richie had a lot of respect from all the underground DJs, claims Danny Krivit. “When he did Studio 54, instead of thinking of him as, ‘Oh you’re just playing that commercial stuff’, we thought of him as someone who does this, but is playing the commercial stuff there. The whole time I knew him he was so down to earth.”

But the music was frequently overshadowed by Studio’s antics: the fucking on the balcony, the industrial quantities of drugs consumed, the celebrity whirlwind. It was more of a show, less of a club. Appropriate given its location. “Studio 54 was like going to see a movie,” says Danny Tenaglia. “It wasn’t about the music, it was a secondary factor. When you went there, it was gimmicky. It was the first club where you had people painting their whole body silver. ‘Oh there was somebody in there on a horse!’ People would talk about that instead of the music. So it was all about who was there: Liza Minelli, Diana Ross. The whole drama at the door of who could get in and who couldn’t.”

Prior to its opening, Rubell and Schrager, who had been running a club out in Queens, were New York unknowns. But Rubell, in particular, revelled in his new-found fame; loved the drugs, the showing off, the power. Kenny Carpenter, another resident DJ there remembers an incident that epitomised his approach. “Rubell brings Calvin Klein, Bianca Jagger and Andy Warhol to the booth. And he says, ‘Can you play ‘Your Love’ by Lime?’ ‘I’m sorry but I don’t have it and it’s not my kind of record.’ He says, ‘Well, listen, I own this club and I’ve got Bianca and Calvin and Andy and they wanna hear that record.’ I said, ‘Listen Steve. Sorry I don’t have that record, but even if I did have it, I wouldn’t play it because it’s not my style.’ He got mad. Stormed out of the booth. The following weekend, he hired Lime to perform live. And he stands looking at the booth, like, now I got Lime.”

As befitted a club of such glorious excess, its stellar years were relatively short. A year after its opening Steve Rubell bragged to the press that, “only the Mafia made more money,” a fact that alerted the tax authorities. The club was raided by the IRS in December 1978, who found $2.5m stashed in garbage bags in the building. The pair were convicted of tax evasion and spent 13 months in jail.

Many people saw Studio 54 as a corrosive presence in disco. “There’s a scene at the end of the Last Days Of Disco where one of the characters has this very idealistic speech where he says disco was a whole movement,” remembers disco writer Vince Aletti. “It was funny, but it was really true and people felt that. They felt disappointed that the idealistic quality of it was being trampled over, in favour of money and celebrity. As much as disco was glitzy and certainly loved celebrity culture when people came to clubs, there was never a sense of it being driven by that. It was much more driven by an underground idea of unity.”

Studio 54 became the template for a certain kind of club, someway from what we’d now regard as the underground. It’s frequently cited as an influence in almost every sleek new entry onto the market, without any of the real glamour and excess achieved by Rubell and Schrager, never mind the heroic levels of drug-taking. When they were released from prison, Schrager opened the Palladium nightclub and went on to build a portfolio of influential boutique hotels. Steve Rubell died of an AIDS-related illness in 1989. In January of this year, Schrager received a full and unconditional pardon from President Obama. He is now entitled to vote.

WORDS: BILL BREWSTER | IMAGE: RICHARD P MANNING and others 26 APRIL 2017 http://po.st/xZrAmI

Ikutaro Kakehashi

Ikutaro Kakehashi, the founder of Roland Corporation, created more than a successful business with a host of important innovations in electronic musical instruments; he has also paid tribute throughout his career to those who first inspired him. Mr. Kakehashi was born in Japan and formed Ace Electronics in 1964 with the goal of improving the electronic organ, following up on the work of his heroes, Mr. Hammond and Mr. Leslie. With the expansion of electronics in the late 1960s, he formed the Roland Corporation, which soon became one of the leaders in the industry. Perhaps the only thing more impressive than Mr. Kakehashi’s success is his own personal energetic passion for music and many, many friends along the way!

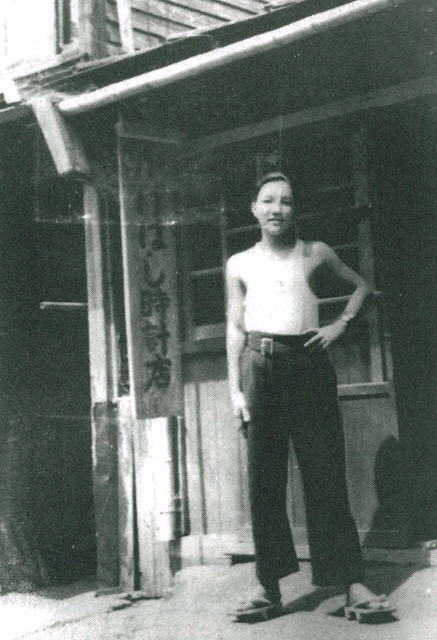

We might not realize it, but the Roland company we know now is entirely different than the one it was shaping up to be in its early days. When Ikutaro Kakehashi, founder of Roland, started his first venture into musical instruments, it was indebted to his love for time. In 1932, at the age of two, Ikutaro lost both of his parents to tuberculosis. As a young boy he had to make a living fixing Kairyu submarines in Hitachi-run Japanese military shipyards. Once the war was over he was refused entry to Osaka’s university on account of his poor health. Searching for a solution to this predicament and a steady job (having been forced to forgo his education) he traveled to Kyushu, the southernmost province of Japan. There, he discovered something brilliant: Post-War Japan had virtually no timepiece industry. Mirroring the beginnings of a young Torakusu Yamaha, he took a job as a watch repairer.

Kakehashi was 16 or 17 years old when he set about to learn in mere months what took years for many to learn through apprenticeships. In mere months, he set up the Kakehashi Watch Shop as a base to start his own ventures. With money raised from repairing watches, Ikutaro turned his eye towards music and the radio industry. Just years ago, even owning or listening to foreign radio transmissions was deemed illegal. Now, here, in Kyushu, Kakehashi was making or repairing devices that were an expression of freedom in Post-World War II Japan. When he finally earned enough money from his shop, Kakehashi turned back to Osaka and decided to use these funds to pay his way back into Osaka University. Unfortunately, once again tragedy struck.

At the age of 20, rather than spend his money on education, Kakehashi had to pay for tuberculosis treatments. For three long years, he was consigned to a hospital ward, only repairing electronics for the hospital staff or other patients in order to support himself. Right before he received Streptomycin, the experimental drug that saved him from his terminal illness, so driven was Kakehashi to view Japan’s first TV signals that he used most of those savings to purchase a vacuum tube to create a television to receive them. In 1954, when Kakehashi finally had the strength to leave, he opened an electric repair shop post haste. In the span of six years, as radio and TV technology grew, he solidified the new business’ name as the Ace Electrical Company and earned enough money to try something different. As the Ace Electrical Company became Ace Electronic Industries, so did a shift toward a new kind of product.

For years, Kakehashi tried to branch out into the music market, following an intriguing product that piqued his interest: the theremin. Influenced by Dr. Bob Moog, Kakehashi tried to build his own theremin. His first creation didn’t sound quite right, but undeterred, Kakehashi moved on to creating a keyboard instrument. Hearing and seeing the Ondes Martenot in action, he used bits from reed organs, telephones and other transistor sound generators to create his own version. This too was another misstep and the instrument never went to production. By 1959, rather than redesign the wheel, he designed and released an organ: the Technics SX601. It was the success of this organ that allowed Ace Electronic Industries to add guitar amps and pedals to its product line. However, by 1963, something new had stirred Kakehashi’s interest: the Wurlitzer Sideman.

Released in 1959, the Sideman was revolutionary in few ways people envisioned. Using tape loops, this self-contained device allowed users to play 12 predetermined drum patterns at varying tempos. A whirling disc would cycle through different electronically generated drum sounds. Using this device, any musician could have drum accompaniment without an actual, physical drummer. However, what interested Kakehashi wasn’t this per se, but the idea of an electronic percussion instrument. In 1964, when he introduced the Rhythm Ace R-1 at NAMM he introduced his version of a drum machine.

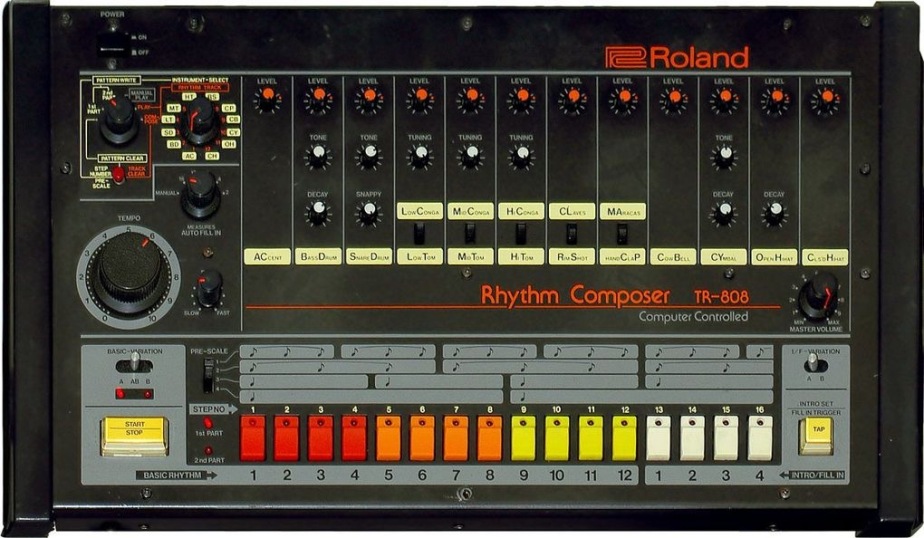

Ikutaro Kakehashi (梯 郁太郎 Kakehashi Ikutarō?, 7 February 1930 – 1 April 2017) was a Japanese engineer, inventor, entrepreneur, and founder of Japanese companies Ace Tone, Roland and ATV. He was a pioneer in electronic musical instruments, involved in developing Ace Tone and Roland drum machines such as the TR-808, TR-909, FR-1, TR-77 and CR-78; the TB-303 bass synthesizer; the MC-8 digital sequencer; Roland synthesizers such as the SH-1000, Jupiter, SH-101, JX-8P, Juno-60, D-50 and JP-8000; the System 700 modular synthesizer; and the MIDI standard, for which he received a Technical Grammy Award. His electronic musical instruments were influential, revolutionizing contemporary popular music and shaping numerous music genres, including electronic, dance, hip hop, R&B and pop music.

Prior to Roland, he started Ace Tone, an electronic organ company that became known for producing early drum machines in the 1960s. It evolved into Hammond Organ Japan, which he eventually left to start Roland in the early 1970s. At Roland, he produced a number of electronic instruments that became widely adopted by the music industry. Kakehashi died in April 2017, at the age of 87.

He was born on February 7 1930 in Osaka, Japan.

Both of his parents died to tuberculosis during his early childhood, leaving him to be raised by his grandparents. Much of his childhood was spent studying electrical engineering and working in the Hitachi shipyards of Osaka. During World War II, his home was destroyed by American bombings. Following the war, he failed to get into university on health grounds in 1946, and then moved to the southern island of Kyushu.

In 1947, at 16 years of age, he founded the Kakehashi Clock Store, a wristwatch repair shop on Kyushu Island. He soon began repairing radios as well.[9] He later returned to Osaka to attend university. During a mass food shortage, he contracted tuberculosis and spent several years in a sanitarium, where he became a clinical trial test patient for an experimental medicine antibiotic drug, Streptomycin, which improved his condition In 1954, Ikutaro Kakehashi started Kakehashi Radio electrical appliance store, while concurrently repairing electronic organs and created new prototype organs throughout the 1950s. At 28, he decided to devote himself to music and pursuit of the ideal electronic musical instrument.

Ikutaro Kakehashi never received any formal musical training. He wanted musical instruments to be accessible for professionals as well as amateurs like himself. He also wanted them to be inexpensive, intuitive, small, and simple. He constructed his first 49-key monophonic organ in 1959, specifically designed to be playable by anyone, with no musical skill necessary. The focus on miniaturization, affordability and simplicity would later become fundamental to product development at Roland.

In 1960, Kakehashi founded Ace Electronic Industries Inc. In 1964, he developed a hand-operated electronic drum, called the R1 Rhythm Ace. It was exhibited at Summer NAMM 1964, however not commercialized. [10] Kakehashi patented the “Automatic Rhythm Performance Device” drum machine in 1967, a preset rhythm-pattern generator using diode matrix circuit, a drum machine where a “plurality of inverting circuits and/or clipper circuits are connected to a counting circuit to synthesize the output signal of the counting circuit” and the “synthesized output signal becomes a desired rhythm.”

Ace Tone commercialized his preset rhythm machine, called the FR-1 Rhythm Ace, in 1967. It offered 16 preset patterns, and four buttons to manually play each instrument sound (cymbal, claves, cowbell and bass drum). The rhythm patterns could also be cascaded together by pushing multiple rhythm buttons simultaneously, and the possible combination of rhythm patterns were more than a hundred (on the later models of Rhythm Ace, the individual volumes of each instrument could be adjusted with the small knobs or faders). In 1968 a joint venture was established with Hammond USA, the FR-1 was adopted by the Hammond Organ Company for incorporation within their latest organ models. In the US, the units were also marketed under the Multivox brand by Peter Sorkin Music Company, and in the UK, marketed under the Bentley Rhythm Ace brand. The unique artificial sounds characteristics of the FR-1 were similar to the later Roland rhythm machines, and featured on electropop music from the late 1970s onwards.[10] Ace Tone popularized the use of drum machines, with the FR-1 Rhythm Ace finding its way into popular music starting in the late 1960s.

Kakehashi also developed the Hammond Piper Autochord, which was a success in 1971. It produced harmonic bass chords from single notes played on the organ keyboard, and was instrumental in the production and domestication of electric organs.

In 1972, he founded Roland Corporation and became president. The company would go on to have a big impact on popular music, and do more to shape electronic music than any other company.[9] At Roland, he continued his work on the development of drum machines. Roland’s first drum machine was the Roland TR-77, released in 1972.[13] The Roland CR-78 in 1978 was the first microprocessor-driven programmable drum machine.[14] These 1970s Roland drum machines were used in disco, R&B, rock and pop songs from the early 1970s to the early 1980s.[13] The most influential drum machine was the TR-808, released in 1980, which was widely adopted in hip hop, electronic and pop music, and is still widely used through to the present day, having been used on more hit records than any other drum machine.[15] The 808 is one of the most influential inventions in popular music.[16][17] It was then followed by the TR-909, released in 1984, which is widely used in electronic dance music, such as techno and house music.[18][19]

He also worked on other influential electronic musical instruments. He developed the the Roland System 700 modular synthesizer, released in 1976.[6] The Roland MC-8 Microcomposer in 1977 was the first stand-alone microprocessor-driven CV/Gate music sequencer,[14][20] and had a significant impact on popular electronic music, with the MC-8 and its descendants impacting popular electronic music production in the 1970s and 1980s more than any other family of sequencers.[21] Roland synthesizers such as the SH-1000, Jupiter, SH-101, JX-8P, Juno-60 and D-50 were widely adopted in popular 1980s music. The Roland TB-303 bass synthesizer was instrumental to acid house music and the rave scene.[4][6] The Roland JP-8000 was widely adopted in 1990s trance music.

In June 1981, Kakehashi proposed the idea of standardization to Oberheim Electronics founder Tom Oberheim, who then talked it over with Sequential Circuits president Dave Smith. In October 1981, Kakehashi, Oberheim and Smith discussed the idea with representatives from Yamaha, Korg and Kawai.[22] In 1983, the MIDI standard was unveiled by Kakehashi and Smith, who both later received Technical Grammy Awards in 2013 for their key roles in the development of MIDI.[23][24] Since its introduction, MIDI has remained the musical instrument industry standard interface through to the present day.[1]

In 1988, Roland purchased Rodgers Organ Company renamed Rodgers Instruments fulfilling Kakehashi’s lifelong dream to build large classical organs

In 1994, Kakehashi founded the Roland Foundation and became Chairman, in 1995 he was appointed chairman of Roland Corporation. In 2001 he resigned from the chairman’s position and was appointed as Special Executive Adviser of Roland Corporation. Kakehashi retired from Roland in 2013.

In 2014, Kakehashi founded the ATV Corporation. [25] Together with Paulo Caius, former CEO of Roland Iberia, Founder and CEO of Roland Systems Group EMEA, Makoto Muroi, a prestigious research engineer for music and audiovisuals, also former President of the Roland Systems Group Japan, Mark Tsuruta, former CEO of Roland Audio Development USA and Glenn Dodson, previous CEO of Roland Australia.

In 1991, based upon his contribution to the development and popularization of electronic instruments, Kakehashi was awarded an honorary doctorate from Berklee College of Music, U.S.A. The Bentley-branded Rhythm Ace inspired the 1997 Birmingham band Bentley Rhythm Ace when a model was found at a car boot sale.

In 2000 he left his handprints at Hollywood’s RockWalk in Hollywood. In 2002 Kakehashi published his autobiography, titled I Believe In Music,[26] and was also featured as a biography in the book The Art of Digital Music. In 2005 Kakehashi was awarded the title of professor emeritus of the Central Music College of China and the University of Glamorgan.

From flop to fame: how the ridiculed Roland TR-808 came to define modern music – WIRED UK

In 1982, Marvin Gaye found himself in the small Belgian city of Ostend, trying to escape his drug, money and family problems. The soul star needed to create his music in complete isolation. He was surrounded by synthesisers and drum machines, pushing buttons, setting levels and cueing rhythms. He pushed “play” on a song that was made entirely using a drum machine. That song was “Sexual Healing”.

The song became a huge global hit, his biggest in years, thanks to a drum machine called the Roland TR-808 Rhythm Composer. After years of being seen as a faded star, Gaye suddenly found himself a key player in a new musical movement.

In an era in which renting studios cost thousands of pounds, Ikutaro Kakehashi wanted to create a tool that would make music-making affordable. Born in Osaka in 1930, he was orphaned at the age of two, and grew up in a Japan between the two world wars. He moved in with his grandparents to the rural island of Kyushu. There he set up a business, repairing clocks and watches, he also started building his own radios so he could listen to radio stations. He was heating old parts over a candle, so the magnesium would oxidise and improve the sound of the tubes. The search for the perfect sound became an obsession, and he dedicated himself to music, via creating experimental rhythm machines. In 1972, Ikutaro founded Roland, releasing, among others the TR-808 drum machine.

The 808 was initially a commercial flop: the sound patterns sounded like a fake analogue instrument, the reproduction of physical instruments to digital sounded too futuristic and the kick drum too overbearing. Seen as a toy in a musical environment where guitars dominated and electronic musicians preferred slicker equipment, Roland discontinued the 808 in 1983.

Its turning point came when its price tag plummeted from $1,200 to $100 – which attracted curious underground musicians from America’s poor urban areas turning 808 into cult. Before long, producers in Chicago, Detroit and New York were making electro, techno, house, acid and hip hop that sounded like nothing else that had come before. Within a few years, Roland’s commercial flop had become an essential piece of kit. It even started its own genre, with acid house being able to have the epithet of acid in front, only if the music was made using an 808.

The rest is history: Madonna’s “Vogue”; Whitney Houston’s “I Wanna Dance With Somebody”; Talking Heads’ “Psycho Killer”; Beastie Boys’ “Licensed to Ill”; LL Cool J and Run-DMC’s crossover smashes… Nearly 30 years later, we can hear the machine’s percussive attack in chart-topping hits from Kanye West and Drake.

Even PC gamers cannot escape from Ikutaro’s legacy, as Roland’s MT-32 sound gave DOS gamers MIDI music. So whenever you connect a keyboard to your laptop, you should thank Ikutaro for creating the technology. (In 2013, Ikutaro received a Technical Grammy Award for his MIDI work.)

How ironic that Ikutaro wanted to enable affordable music, only for the TR-808 to be unaffordable for fledgling musicians. It took its initial failure to become a huge success. And today? Turn your radio on and you’ll hear an 808 kick in within ten minutes. And for this, Ikutaro arigato.

Source https://apple.news/AvBZYVYsHSiu5tfNmGhPjxA

Sound Devices launches new audio recorders/mixers with USB audio streaming – Pro Video Coalition

At NAB 2017, Sound Devices has announced the new MixPre Series of audio mixer/recorders with integrated USB audio interface. The lightweight, high-resolution MixPre-3 & MixPre-6 audio mixers recorders with USB audio streaming offer hefty preamps combined with extreme durability.

The new Kashmir microphone preamps have much more gain than competitive units, as I’ll cover ahead. They also feature a published -130dBV noise floor, analog limiters, and new 32-bit A-to-D converters to ensure high quality, stress-free, professional-grade audio recordings. I hope to review one very soon. Ahead is more info and a video.

For dynamic mics, at least +60 dB is considered a bare minimum, and even more for an ElectroVoice RE20 or Shure SM7B to avoid having to max out the potentiometers, or avoid having to purchase a FetHead or CloudLifter for each source.

“Our new Sound Devices MixPre Series is the culmination of decades of experience designing products for the best-of-the-best in the professional audio industry,” says Matt Anderson, CEO of Sound Devices, LLC. “Our mic preamps simply have to be heard to be believed, whether mic’ing drums, birds, or dialog, using condenser, dynamic, or ribbon mics, the finest textures of the audio are preserved. The MixPre-3 and MixPre-6 merge the latest advances in audio technology with an unintimidating, compact and rugged design. These products are a must-have piece of equipment for anyone ranging from production engineers and musicians to YouTubers.”

https://apple.news/AiRsmVN1nMWiHMFp3SN9Hmw

Vinyl is back. But until now, record-making has been stuck in the ’80s. – Popular Science

Just over two years ago, Rob Brown was transfixed by an eBay auction. He and colleagues Chad Brown (no relation) and James Hashmi were bidding on a record pressing machine. It was the only one the new entrepreneurs could find, and it was in the middle of nowhere—in Russia. No one knew if it worked, or could even be refurbished back into working order. Yet, the bidding was feverish: Brown’s team walked away, but the press ultimately sold for some $60,000.

So went the shopping experience of anyone looking to open up a pressing plant amid the vinyl resurgence of the last decade. No company had made a new record press since the ‘80s, and used ones were nearly impossible to find. Longstanding plants, like United Record Pressing in Nashville (the largest facility in the U.S.), would absorb equipment from shuttering competitors. And upstarts would have to either wait out the second-hand market or build their own from scratch.

But Brown, Brown, and Hashmi wanted to get their hands on a press for a different reason. They wanted it as reference, a benchmark against which to measure the singular goal of their Toronto company, Viryl Technologies: to build the first new fully automated record pressing machines in over 30 years. Thanks to carefully orchestrated automation and cloud-based monitoring software, their WarmTone presses were going to be easier to use and simpler to service—and therefore more-efficient—than their hulking hydraulic predecessors.

Record Scratch

Even in the best circumstances, making a record is a laborious process. There are machines to cut studio recordings into a master version of the audio, then another set to create a metal negative plate of the master for the giant waffle iron that is a record press. The biggest piece of the puzzle, literally and figuratively, is the pressing machine itself, which stamps out copy after copy after copy.

The number of workers trained to use and repair the machines dwindled when record sales bottomed out and plants began shutting down in the early ‘90s. Facilities that did retain skilled pressmen held onto personnel (and their expertise) with a firm grip. “There’s just not a lot of people doing it,” says Jonathan Berlin, owner and partner at Vinyl Record Pressing in Atlantic Beach, Fla. “The people that are doing it want to be the only ones doing it.”

Workers learn the ins and outs of their machinery, its quirks, and its red flags. And, because most plants contain a mashup of presses—recycled, revamped, and reengineered with modern components—there’s little, if anything, in the way of manuals or guides. “Because the industry had died off, and the companies that produced the presses were all long gone, there really is no level of service left,” says Rob Brown, Viryl’s chief operations officer. Breakdowns are common, and fixes tricky.

This largely bespoke approach has contributed to a problem: For years, vinyl production has been at or over capacity. According to U.K. research firm Deloitte, total record sales in 2017 will hit 40 million worldwide. And Nielsen’s 2016 Year-End Music Report showed the eleventh straight year of consistent upswing. That’s a lot of discs for the few dozen up-and-running plants and couple hundred or so working presses worldwide.

It’s so many records, in fact, that about two years ago United stopped taking on new clients for about a year to clear up its backlog and shorten turnaround times. For smaller shops and upstarts, backups are harder to manage—and sometimes exacerbated by the run-up to major selling seasons.

Source- Corinne Iozzio Popular Science

Knops earplugs turn down the disco so you can hear it clear – Stuff

Time was, tuning out the louds sounds of life meant stuffing some rubber plugs in your canals. Effective as the trusty bungs were, though, pulling them out for a quick chinwag was a right hassle. Thankfully, Knops has served up an adjustable solution on Kickstarter: stick its circular sound-stoppers in your ears and you’ll be able to control just how much sound gets in by twiddling the dials – whether that’s blocking out the bus drunk’s dystopian ramblings or letting in a little more bass at the office party. It’ll still sound crisp and clear, mind, as there’s no digital trickery going on: the plugs’ physical construction does all the magic, distortion-free.

https://apple.news/AKDv7JJd9SXGEFaQUNoCj5A

AudioQuest JitterBug: Can a USB Filter Really Improve Your Audio? – GeekDad

The AudioQuest JitterBug isn’t a new pair of headphones with better speakers. It’s not an amp to boost the robustness of the sound being delivered to your headphones, and it’s not a DAC, trying to deliver the highest-resolution signals to your amp and headphones. It’s much more esoteric: it’s a filter for your USB port.

First, backing up: if you’re getting into higher-quality sound, delivered from your laptop or desktop computer, the first thing you learn is that you don’t want to listen to the music from the mic port. The on-board mic ports on most computers are using a very basic DAC (digital-to-analog converter) to change the bits of your sound files into analog audio signals going into your headphones or speakers. Instead, you plug a higher-grade DAC into a USB port. Then you probably plug an AMP into that, to boost the resulting signal (or the DAC and Amp are a combo unit). And then you plug your headphones/speakers into that for listening nirvana.

But the audiophile engineers at AudioQuest, ever looking for ways to improve the resulting sound just a little bit more, hit upon one of the weak points in this sonic workflow: the quality of the signal coming out of the USB port. Most people just think data is data, and if you’re getting a steady stream of 1s and 0s that isn’t doing anything special until the DAC turns it into analog signals, then what can you do to improve it

https://apple.news/A6SM-GbeTMRO4jascj6n7bw